Drafts and Revisions

After all the preparation that has gone into a paper, all the research, all the thought, and all the hours spent writing it, there is often nothing students would rather do than hand in their first draft and be done already! Our advice: resist the temptation of handing in a first draft.

Too often, first drafts read like papers written the night before they were due (see Time Management) - they tend to be full of typos and are sometimes marked by poor style, weak theses, poor organization, and lame conclusions. Avoid this by allowing sufficient time for second and even third drafts, and ongoing revisions.

Time allowing, you should set a first draft of a paper aside for a day or so, then re-read it with "fresh" eyes - perhaps even have a friend proof-read it or you. Chances are you will immediately spot awkwardly-worded passages, typos, stylistic glitches and other "surface" errors that require editing (on such basic surface errors, see Common Stylistic Errors).

Having attained some critical distance from your own work, re-reading it may also heighten your awareness of more deep-seated problems: perhaps your thesis (or conclusion) is not as effective as you initially believed; perhaps your examples and evidence are less compellingly presented than you'd hoped; perhaps your overarching argument now seems less convincing than it did at first. If you notice these things, your professor will notice them too; the time to address them is now, before handing in the paper. Once you receive it back with a lesser grade than you'd hoped for, it is too late. Therefore, before handing in your paper, review the material in Developing a Thesis, Organization, and Formulating a Conclusion - all in the Preparation and Writing section of this website.

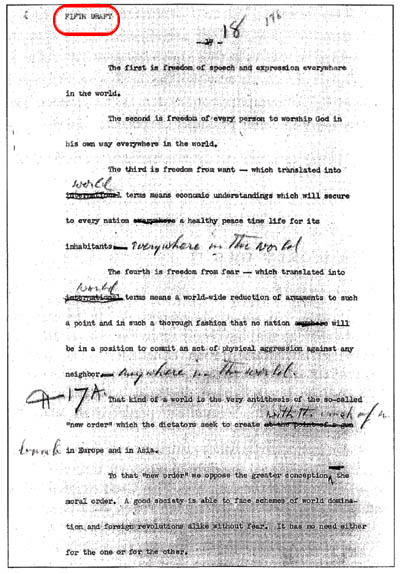

On a final note, we can think of no better argument for drafts and revisions than pointing out that even Franklin D. Roosevelt, one of the great wordsmiths of the twentieth century, carefully polished and revised his speeches and writings. At right, we have reproduced a page from his famous "Four Freedoms"-speech of January 1941. Towards the end of this speech, FDR enumerates the "four freedoms" for which, he says, it is worth going to war: freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom from want (poverty), and freedom from fear. Clearly, FDR spent considerable time and effort getting this all-important, oft-quoted passage just right.

If even a four-time president of the United States saw fit to edit and revise his work, shouldn't you?

For the full speech, please click here.